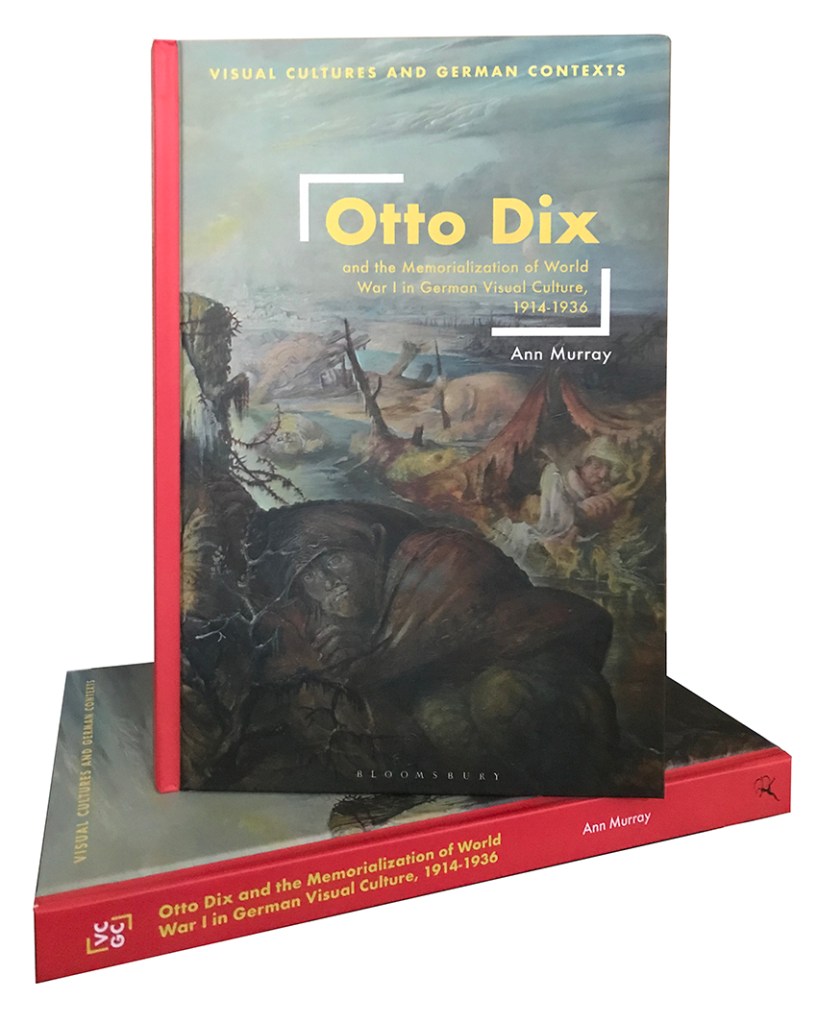

Otto Dix and the Memorialisation of World War I in German Visual Culture, 1914-1936

(Bloomsbury, Visual Cultures and German Contexts, 2023) Paperback, eBook and hardback. More information on the publisher’s website (opens in new tab).

This book, supported by a Royal Irish Academy Charlemont Grant, explores the role of Otto Dix’s confrontational pictures in shaping the memory of World War I in Germany during the years 1914-34, analysing how their meaning as war memory was defined by the visual culture of war that surrounded them, Dix’s artistic peers and critics.

Chapter Descriptions (Excerpt from the Introduction)

Each chapter, except Chapter 1, is built around the visual and contextual analysis

of one or more key war-related works at the time of their first public exhibition.

In addition to so-called expert insights and opinions in dedicated art-historical

and cultural publications of the years in question, reviews in the popular press,

including local newspapers and magazines, shed further light on how the works

were received more generally. Some of the figures who responded to Dix’s work

were among the most prominent of the time and their histories are well known,

such as Carl Einstein, Paul Ferdinand Schmidt and Paul Westheim. Others are

forgotten, or little is known about them. While the perspectives of the latter,

or their relative abilities as cultural commentators is lesser known, their voices

enable a more deeply textured insight to the reception of Dix’s work, sometimes

contesting the opinions of established art and cultural critics with regard to how

Dix’s war art engaged with debates, or even mattered, in shaping the cultural

memory of the war.

In addition to focusing on major works, the book accounts for the overall

content of the artist’s war art during the years in question in terms of theme

and style and known surviving critical reviews of them. The definition of what

qualifies as ‘war-related’ imagery is somewhat problematic, but for this book

that definition is work that includes imagery of military figures and materiel,

veterans, symbolic works and places directly connected with the experience

of war. Illustrations have been necessarily limited to works most discussed in

the text. In cases where a work cannot be illustrated, its location is listed. In

most cases, such as those which are housed in cultural institutions, high-quality

reproductions are available on their websites.

Referencing Dix’s wartime correspondence, among other sources,

Chapter 1 explores a cross-section of the artist’s almost 600 wartime pictures in

relation to his experience as a frontline fighter – the essential key to his postwar

memorialization of the conflict – from his thirteen months of training at

Bautzen, near Dresden, to his initial activities on return from war duties in

1918–19, and includes his rarely referenced first-ever public exhibition of his

war pictures – his first foray into publicly commemorating the war. I begin

by examining some of the earliest pieces, the four pre-battlefield self-portraits

and the first battlefield self-portraits, which reveal the disparity between Dix’s

self-portrayal as soldier before and after arriving on the battlefield, recalling the

heady idealism and subsequent cynicism of many of those who volunteered.

From his portrait as Mars, which epitomized the Nietzschean (and subsequently

Futurist) notion of escaping the constraints of society and regenerating oneself

through the speed and chaos of warfare, to the first self-portraits made in the

trenches, a considerable stylistic and apparently ideological change occurred

in Dix’s self-portrayal. The chapter then looks at works that chart the artist’s

remarkable artistic growth, through continuing experimentation with a range

of stylistic approaches and subject matter. The first public exhibition of his war

art (and the first-ever public showing of his work) in Dresden in late 1916,

as part of a major exhibition of work by soldiers serving in the Saxon Army,

contextualizes his work alongside that of his peers, such as the ‘star’ of the

Dresden show, Otto Schubert. Schubert, and others exhibiting in wartime

shows, established a mode of memorialization that in its portrayal of the

harshest aspects of war was at odds with the tradition of German war art to

date. Exposure to such work possibly shaped Dix’s public articulation of the war

experience beyond 1918, guiding him towards a mode of memorialization that

could more forcefully probe public opinion on warfare and how the war should

be remembered.

Chapter 2 focuses on the artist’s portrayal of the war amputee as the antiicon

of German war memorialization, in four major pictures created in the years

1919–20, alongside other key works, and their role in shaping war memory in

the immediate post-war years. The transformative impact on Dix of the Berlin

Dadaists – cholerically critical of those responsible for involving Germany in the

war – led to a purposeful visual language that engaged directly with post-war

societal vicissitudes. The reception of the works as part of the First International

Dada Fair, among other exhibitions, is considered in relation to the turbulent

sociopolitical background.

Chapter 3 analyses the context surrounding the first public exhibition of

the now-lost Trench, first shown in late 1923, and The War, the suite of fifty

intaglios detailing various facets of the war experience, shown for the first

time in mid-1924. This longer chapter reflects the high watermark in critical

interest in Dix’s art, revealed in the number of reviews and critical sparring

with regard to The Trench’s visualization of the war experience. The controversy

surrounding The Trench’s voraciously realistic memorialization of the worst

effects of trench warfare on German soldiers revealed the troubled nature of

war commemoration in Germany. Numerous reviews of The Trench and The

War, in some cases lengthy, are reproduced for their significant insight into the

impact of the works and because they are not usually reproduced in English. The

exhibition of The War in Germany and internationally, and the reproduction

of some of the etchings in anti-war publications, marked the first widespread

dissemination of Dix’s war art in print media.

Chapter 4 focuses on the triptych Metropolis, at the time of its first public

exhibition as part of the show, Saxon Art of Our Time in Dresden in 1928, amid

the wave of renewed interest in the war due to the tenth anniversary of the

Armistice. Though the triptych is not generally read in terms of war memory,

the chapter shows how it communicated the war’s lingering effects through

the intermediary figure of the war amputee. The work is explored through the

context of Dresden’s cultural and political life, where the emergence of a number

of politically motivated, opposing artists’ groups reflected the polarization of

cultural life in line with politics. The targeting of Metropolis as culturally and

politically undesirable, in part because of its representation of war veterans,

by the extreme nationalist artists’ group, the German Art Society Dresden

(Deutsche Kunstgesellschaft Dresden, DKD), led by Bettina Feistel-Rohmeder

and which counted Dix’s colleague Richard Müller as a long-time member,

reflected the emergence of a strong, if still uninfluential, cohort who intensified

their campaign against modernist artists. Well connected to NSDAP politicians and supporters, the DKD also pilloried Dix personally in their German Art

Bulletin, funded by extreme right-wing supporters in Dresden. The DKD’s

interest in Dix’s art is a rarely examined facet of Dix’s career, but consideration

of their criticism of Metropolis complicates its reception and broadens insight to

how it engaged with its audience as war memory.

Chapter 5 treats Dix’s major battlefield triptych War. Begun around 1927–8,

the picture is often seen as a product of the renewed interest in World War I

during the decade commemorations. But by the time the picture was first publicly

exhibited in Berlin in late 1932, the country had seen many organized marches

and protests by political and cultural groups as means to voice their views on

the war and in some cases counter the growing support for the militant NSDAP.

The humanity of Dix’s imagery of tattered, vulnerable everyman figures, hardly

recognizable as German soldiers, reflected the attempts of liberal and anti-war

bodies, through public protest and various media outlets, to remind the public

of the consequences of militarized society and urge rejection of the NSDAP’s

excessively chauvinistic patriotism. Yet, as the chapter shows, War failed to make

the impression that The Trench had almost a decade earlier.

Chapter 6 looks at the fate of the war pictures – reflective of the fate of Dix’s

work overall – after the NSDAP came to power in January 1933. Particular

focus is given to the Degenerate Art Exhibition in Dresden in late 1933, a show

that counted three artists as its organizers, Richard Müller, Willy Waldapfel

and Walther Gasch, and who spotlighted Dix’s War Cripples and The Trench

as the high watermark of degeneracy. The chapter also looks at how the works

continued to be exhibited and discussed, sometimes beyond German borders,

even though Dix was banned from exhibiting in 1934.

The book closes with a word on the artist’s activities up to the outbreak of

World War II, including the exhibition of Flanders (1933/4–6) as part of a major

exhibition of the artist’s work in Zurich in 1938, and the comparative fate of

some of Dix’s contemporaries under the Nazi regime.